The image has become a classic in our pop culture lexicon: Charlton Heston, arms outstretched, robe billowing about him as if wrapped in a thundercloud. He turns from the teeming masses below him toward the sea and, with a voice equal parts prophet and politician, cries out, “Behold his mighty hand.” The sea parts. People cross on dry land. Music swells. “ABC’s presentation of ‘The Ten Commandments’ will conclude after these messages.” Thankful for the brief interlude, we race to relieve our bladders.

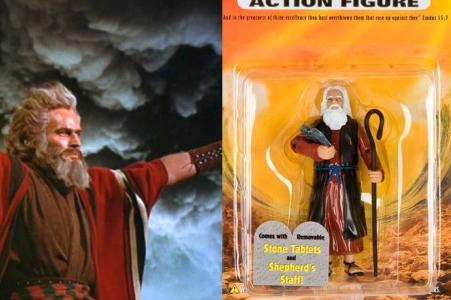

The great irony of the Moses mythology is how its constant retelling risks rendering it stale and distant from present realities. By venerating the myth, in whole or in part, our culture drains it of its pulse and reduces it to archaic mental images and stock photographs of Charlton Heston with a full beard and long wooden staff. Moses’ tale, told each year in the Passover Seder, has been regurgitated by pop philosophers, stage producers and artists. In so doing, Moses is both elevated to a place of status and reduced beyond his simple humanity.

Rabbi Maurice Harris’ new book “Moses: A Stranger Among Us,” seeks to reclaim the narrative beats of the life of Moses for modern spiritual consumption.Yet Harris, a graduate of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, did not initially approach the tale of Judaism’s central prophet with this problem in mind. Instead, his own relationship to the Moses story underwent several changes over the course of his life prior to writing the book, the most influential of which brought on by parenthood. “We’re the adoptive parents of two kids who were in foster care for a number of years,” Harris explained in an interview with New Voices. “They were older when they became our kids. They were not Jewish by birth. All of a sudden, they find themselves in this rabbinic family.”

Harris and his wife were struck by the reaction of his children to stories of Moses’ life: “What they noticed right away was, ‘Oh, he was adopted,’ and that he’d also been a baby during a time when there was a lot of violence and trauma happening all around him – and that that violence and trauma had completely blown apart his first family and resulted in him having a different destiny,” he said.

By seeing the tale through these youthful eyes, Harris felt a shift in his own relationship to the familiar character of Moses, one which reflects Harris’ call toward creating inclusive Jewish experiences – toward converts, interfaith families and others with non-traditional backgrounds who passionately engage Judaism. In “A Stranger Among Us,” Moses is identified as an intermarried man (his wife, initially a non-Jew, was retroactively made a convert by the rabbis of the Talmud, a development Harris simultaneously acknowledges and dismisses); the father of an open system of Judaism which accepts outside influences from non-Jews; and the product of the civil disobedience of women to patriarchal, oppressive authority, among other things.

Harris’ argument that Moses was intermarried is particularly interesting, as he chooses to frame the prophet’s engagement with his own tradition as secondary to the zeal of his wife. He writes, “Tzipporah’s quick action to circumcise her son brings to mind something we rabbis often see in contemporary intermarriages: families in which the non-Jewish partner, especially the woman in a heterosexual marriage, is the one who becomes knowledgeable about Jewish traditions and takes the lead in ensuring they’re being observed and passed on to the children.” Harris continues by emphasizing a reaction to intermarriage that is based much more on a careful study on the phenomenon itself, rather than on the fears associated with it—assimilation, for one.

“I think the Jewish community for many years has used a framework for talking about intermarriage that I call a framework of costs,” Harris explained during our recent interview. “In other words, the only question they really ask is ‘How many Jews down the line is this going to cost us?’ So then they come up with different answers and different positions about how to respond to intermarriage based on that framework of costs. What I try to say is that the framework of costs is the wrong framework, and that it mislabels the phenomenon of intermarriage, and that a better framework—a healthier framework—is to look at intermarriage as a complex phenomenon with costs and benefits.”

Harris goes on to describe a way of looking at intermarriage that respects what non-Jewish partners bring to the fabric of Judaism. This is an idea that appears more than once throughout the text of “A Stranger Among Us,” from his description of Judaism as a “creative open system” that is enhanced rather than degraded by the sharing of outside ideas and perspectives, to his emphasis on the role of non-Jews in the life and well-being of Moses. Harris’ depiction of the Prophet is squarely in the narrative of pluralism, tolerance and diversity. This Moses is as authetically Jewish as he is culturally Egyptian, as indebted to the contributions of the Hebrews as to the insights of the Midianites.

That’s not to suggest that Harris belabors the text with interpretations it can’t support. Hardly; his deep familiarity with Torah undergirds every argument he presents, and he is a persuasive writer. Nevertheless, this Moses seems definitively modern, a creative reinvention rather than an attempt to understand the intention of the myth’s original scribes. It is all the more engaging for it, a version of Moses that chips away at the brutal, cold, or merely impersonal iconography that have characterized Moses in many circles.

Harris’ writing style is clear and concise. “A Stranger Among Us” is a tight, accessible read: only 164 pages. But the miracle of this book is less its portrayal of Moses than its ability to work as both serious theology and general reading. “Stranger” succeeds as it presents meaty ideas to the layperson without a condescending—or, conversely, an overly academic—voice. Within a few unassuming pages, Harris makes some of the best arguments for contemporary liberal Judaism I’ve read since Rabbi Mark Washofsky attempted to codify Reform practice in “Jewish Living.”

Chapter seven, “The Law of Moses Can Be Challenged and Changed,” explains the logic of adapting Judaism to continue to speak to modern spiritual and intellectual times. Harris writes, “So if the law can change, can it change in any which way? I don’t think that’s what these passages from the Torah are trying to teach. The law changes in response to appeals for change based on claims of justice.” Harris continues this intriguing section by responding to common arguments for or against certain types of change in the Jewish community. The dialogical approach here, even for a few pages, gives the arguments room to breathe and reinforces a sense that Harris wants his ideas to challenge and be challenged.

Theologians, philosophers and students of social theories will find much to chew on, even as newcomers will gain a sense of what basic Jewish thought is about. Those unfamiliar with midrash, the Jewish tradition of storytelling to expand on the plain meaning of Biblical passages, will get a crash course in the subject. The book carries an introduction by a Christian pastor who explains how the book’s relevance extends beyond the Jewish community. This may be especially reassuring to non-Jews shaken by Harris’ willingness to play fast and loose with the creative storytelling, a form of teaching less common in certain Christian sects, where it can be seen as icompatible with faithfulness to the original text.

The book carries the distinct hallmarks of a Jewish enterprise, even as it reaches outside our walls. Within is explored the art of reinventing Torah, of telling stories about our stories, of choosing to stand at a different angle when approaching these myths—if only to see what vantage point it affords us. Those outside the Jewish community will be given a window into a spiritual practice that is as important to our continuity as the most precious ritual observances. This makes “Moses: A Stranger Among Us” one of the most enjoyable, earnest and truly relevant theological undertakings this year—a delight from page to page, and a sincere examination worthy of the Prophet himself.