Lift your head from the haggadah. Where is Pharaoh’s army today?

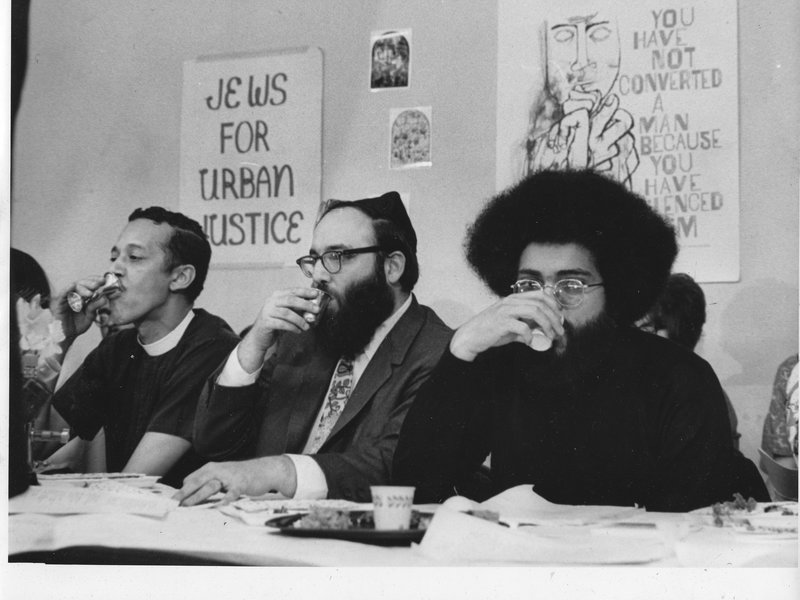

This inquiry motivated Rabbi Arthur Waskow to create the first Freedom Seder. After Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s April 1968 assassination, Waskow saw the police occupation of black neighborhoods in DC and other cities nationwide as an uncanny parallel to the Passover story. The next year, Waskow hosted the first Freedom Seder in Washington, DC with a group of Black and Jewish activists. He created a new haggadah, which detailed the biblical Jewish exodus from slavery alongside the history of US racism and slavery. This Seder was a revelation, Waskow told New Voices. “I realized that the seder was in the streets; the streets were the seder.”

Social justice-related Passover content today seems ubiquitous; haggadot about queer liberation, environmental equity, and racial justice likely graced many of our Seder tables this weekend. But Rabbi Arthur Waskow, a Philadelphia-based radical faith leader, explains that this was not always the case. Though most Jewish organizations now embrace modern-day takes on Passover, Waskow says that many Jewish leaders initially disapproved of the Freedom Seder. “They said to me, ‘There already exists a haggadah!’”

Waskow remembers that when he hosted the first-ever college campus Freedom Seder at Cornell in 1970, over 2,000 people crowded into the school’s fieldhouse to break matzah –– but Cornell’s Jewish institutions did not officially sponsor the event. This 1970 Freedom Seder was a preview for the ways campus Jewish organizations struggle to reconcile the story of Passover with the fight for freedom in our own time. In conversations about the Women’s March and Movement for Black Lives, Jewish groups agonize about whether we should stay in coalition with other marginalized groups when differences over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict arise.

In this context, the Freedom Seder seems a useful parable for the most pressing questions facing Jewish life on campus. When groups such as Hillel and J Street U refuse to host events with most pro-Palestinian student organizations, they prevent Jewish students from building relationships and coalitions necessary to fight white supremacy, regardless of our opinions on Israel-Palestine.

In particular, the history of the Freedom Seder at my own Northwestern University proves that instead of engaging with difficult questions around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, campus Jewish institutions frequently choose to defend their pro-Israel stance at all costs. The contentious campus history of the Freedom Seder should remind Jewish institutions this Passover to recommit to justice and solidarity, instead of actively excluding students of color and Jewish students who criticize Israel.

In 1971, The Daily Northwestern offered a brief advertisement for Waskow’s Freedom Seder haggadah: “You saw it condemned by the Jewish Establishment. Now you can buy the “Freedom Seder” at Hillel.” (They enticed cash-strapped students with a “Special Price”). The first Freedom Seder at Northwestern occurred in 2003 as a collaboration between Hillel and For Members Only, the black student union. The event was not actually held on Passover (attendees ate leavened bread) but referenced the Jewish holiday to frame discussions of historic Black-Jewish coalitions during the Civil Rights Movement. A version of this event continued on campus between 2003 and 2014.

The Freedom Seder at NU ceased after 2015, when the Associated Student Government successfully passed a resolution to divest from companies profiting from human rights violations in Israel and Palestine. When I arrived at NU the following September as a first-year student, I was told that hosting a Freedom Seder was now impossible because of the divestment vote.

NU’s divestment vote divided Jewish institutions from affinity spaces and groups led by students of color. FMO, the former co-sponsor of the Freedom Seder, joined the NUDivest coalition. On the other side of the debate, a coalition formed to oppose the divestment resolution. That group, NU Coalition for Peace, was largely made up of students in the Hillel-affiliated J Street U and Wildcats for Israel, as well as members of AEPi. Hillel International’s political guidelines put Jewish students involved with Hillel in a bind –– they could not publicly partner with those who supported divestment without violating Hillel’s standards of partnership.

The Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement both explicitly and implicitly drew lines in the sand between Jewish and Black groups at NU. I have rarely, if ever, seen a Jewish group on campus sponsor or host an event with FMO in the last four years. Nor have Jewish groups acknowledged with the extent to which they have stepped back from building coalitions with communities of color. In 2016, a private prison divestment campaign called Unshackle NU received no campus Jewish institutional support or endorsement.

A group of students are now attempting to revitalize the Freedom Seder at NU, and we have been consistently met with push-back from Jewish institutions. Our group felt it was impossible to host a Freedom Seder that ignored the Israeli-Palestinian conflict –– in a practical sense, how would we purport to rebuild the relationships between Black and Jewish students on campus without acknowledging a central reason (i.e. divestment) those relationships are strained?

At first Hillel and J Street U were willing to co-sponsor a liberation seder. But when we began to compile our own haggadah that calls for fighting white supremacy through collective liberation, and when our group insisted we discuss Palestinian liberation in partnership with Students for Justice in Palestine, Hillel and J Street U relinquished their official support for the Freedom Seder.

J Street U leadership told us that the group was not permitted to co-sponsor events with SJP, for reasons which seem to be nebulously justified in the group’s official policy. (Other campuses have hosted events between J Street and SJP, such as Bryn Mawr). By contrast, Hillel International’s standards of partnership do not just prohibit conversation with groups that support divestment, effectively shutting down official spaces for dialogue between Jewish and pro-Palestinian students on campus. These standards also preclude Hillel from working with campus groups that “Exhibit a pattern of disruptive behavior towards campus events or guest speakers or foster an atmosphere of incivility.” This not-so-coded language preventing Hillel from working with “disruptive” students means that activists in our group, whether a part of SJP or FMO, would not be allowed to be an official part of the Seder if Hillel were a sponsor.

In the wake of constant Jewish outrage at Black solidarity with the Palestinian cause over the past year –– whether regarding divestment, the Women’s March, or Rep. Ilhan Omar –– this year’s Freedom Seder is an opportunity to speak across divides and address the issues that frustrate our attempts at intercommunal solidarity. But across the country and on campuses beyond NU, the standards of partnership preclude Hillel from sponsoring a Seder which brings together Black, Jewish, and Palestinian students to actually discuss what liberation and freedom might mean to each of our (often overlapping) communities.

Campus Jewish institutions would do well to take a page from Rabbi Waskow’s haggadah. His 1969 and 1970 Freedom Seders reminded us that our liberation requires building solidarity with non-Jewish communities. The Freedom Seder at its core challenges us to speak to, not avoid, that which divides our coalitions. That major Jewish institutions instead have chosen to opt-out both hurts my heart, and also deeply worries me. In a time of rising white supremacy and of anti-Semitic and Islamophobic violence, I fear the consequence of Jewish groups walking away from coalitions because of Israel and Palestine.

Rabbi Waskow reminds us that there are no shortage of Pharoahs in our time. In attempting to revive the Freedom Seder on NU’s campus this year, it has become ever more clear to me that we cannot shy away from conversations about Israel and Palestine when we discuss freedom and liberation. Instead of removing support from an event that seeks to bring student activists together, Jewish organizations should support young Jews’ desire to have conversations in the face of our seemingly-insurmountable political differences. We as students have chosen to create a Freedom Seder that demands collective, not partial or selective, liberation. I hope that Hillel and J Street U will join us.

Jess Schwalb is a 2019 New Voices Fellow at Jewish Currents. She is from Washington, DC and currently studies history at Northwestern. Whether organizing with Chicago’s Jewish Council on Urban Affairs or leading The Daily Northwestern’s Opinion desk, she has found both meaning and community in interrogating stories about American Jewish communal memory and challenging national perceptions of young Jewish life.

Featured image credit: NPR.org.