i. Tevye Comes to Brooklyn

My dad and I read Sholem Aleichem when I’m young. He has a copy of Tevye the Dairyman and the Railroad Stories, but we stick to Tevye. We sit on the couch and he reads out loud to me. I grow up on Aleichem, not Fiddler on the Roof; my memory today is blurry, but I don’t think I see Fiddler until after we’ve read the stories. Even so, I don’t remember it very well.

Tevye is bookended by two other parental reads: the Little House on the Prairie series, with my mother, and Arthur Miller’s Focus, which I ask my dad if I can read, to the answer not until you’re thirteen. I wait. Then I read it. The passage I have always remembered best is the recounting of the story of Itzik, who is not unlike Tevye and the people of Boiberik. Itzik is ordered to take money back by a baron overthrown by his serfs. It’s clear to Itzik that this is a pretext for the baron not only to take the money back, but to blame the Jew: In short, he saw a pogrom in the making. It’s a story about why the Jews did not leave tsarist Poland, told in a book about why the Jews did not leave 1940s America. What could this Itzik do? Only what he had to do. And what he had to do would end up the way he knew it would end up, and there was nothing else he could do, and there was no other end possible. That’s what it means.

At this time, my family history is vague to me: I know mainly that my great-grandfather Irving was an immigrant; he left in the 1890s as a small child to come to New York. His Ellis Island certificate says he was from Russia. What it means by Russia: The Pale. He could have been from anywhere. What it means by Russia is the graves are gone, and we don’t know how to find them again.

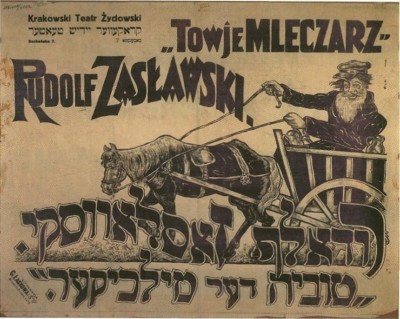

ii. Tevye Makes His Screen Debut

In the summer bridging first and second year of university, I declare my academic plan: major in history, minor in Jewish studies. It seems natural. I have always loved history, and I became much closer to and loving of my Jewish heritage over first year.

My dad takes me to see a documentary on Sholem Aleichem: Laughing in the Darkness, and we do. Afterwards he asks me if I still want to minor in Jewish studies. I look at him, surprised, and laugh in the Manhattan night. Of course I do. Why would that change my mind? The film opened me: The world is so rich. My history is so rich, and it is mine. It stretches out in front of me, no end and no beginning, waiting for me to put my finger somewhere on the timeline and the map. This is what I love about history: anywhere and anytime, someone is waiting for me.

iii. Tevye Kills the Constable

My friends and I decide one April night in 2013 to watch Fiddler on the Roof. This is the first time I’ve really seen it. The movie bears so little resemblance to the stories I grew up with, but I love it anyway.

Tzeitel gets married. The soldiers and the constable arrive to turn a party into a pogrom. As the violence fades out, as Tevye cleans up, my friend throws a blanket over my face.

Don’t move, she says. I try to peek out. She’s holding something rolled up. Don’t look.

The constable is holding a newspaper above my head. The constable strikes at the wall and puts his hand on my head so I won’t move, won’t look, won’t do anything. Can’t move, can’t look, can’t do anything.

What the fuck is going on, I ask. I laugh. High-pitched. Panicked.

No one will answer me.

When the constable takes the blanket off my head, she tells me there was a house centipede crawling along the wall just behind me. She knows I hate bugs. She didn’t want me to freak out.

iv. Tevye Demands a Better Answer

I take my dad’s copy of Tevye the Dairyman to reread. I start with the introduction and am struck a few pages in when the translator, Hillel Halkin, writes about arguing with God in the face of suffering.

But there is also, as we have seen, a fourth possible response: God exists; He is good; He is all-powerful; therefore He must be just; but He is not just; therefore He owes man an explanation and man must demand it from Him. This is Job’s response. And it is also Tevye’s.

My relationship to God has always been vague. I believe idly. If someone asked, which people rarely do, I would describe myself at this time as a true agnostic — I don’t believe God’s existence can be proved or disproved, and I don’t know if I believe or not anyway. I’m a consistent Libra, if you like, always in the act of balancing my own scales. I’m a consistent Jew, if you like, arguing with myself about everything.

We invent explanations when we suffer. I’m no different. Sometimes the explanation is God. Sometimes the explanation is the Devil, or the Adversary. Sometimes the explanation is the absence of order in a Godless universe.

Sometimes the explanation is that we are owed one.

v. Tevye Visits His Old Friend’s Grave

In August of 2014, my dad and I finally go to Mount Carmel Cemetery, where one pair of his great-grandparents are buried. He’s wanted to take me here since we moved to Ridgewood last year. There’s something else too, he says. Another relative? I ask. He won’t tell me, just says we’ll go look after the Mendelows.

We spend a few minutes at their graves. I take photos; I don’t know when I’ll be back. Two years ago, we stopped in Oneonta to see Irving’s grave. His wife, Rhea, lies beside him. I took photos of those, too. That time, we put stones on the graves. There are no stones to find here and I feel a little empty.

I follow my dad through the maze of headstones. We walk the wrong way at one point, but then he corrects course. Soon I find myself standing in front of Sholem Aleichem’s grave.

There are stones everywhere on the grave. People like me make pilgrimages here, I imagine. I am not the only person who carries Sholem Aleichem in my head.

The sun is bright overhead. I think about Tevye.

vi. Tevye Stays Put

I visit my best friend in Grande Prairie, Alberta. While there, I notice on the main highway a sign that points to Alaska. It’s the furthest north I’ve ever been, nearly the furthest west. I tell my dad about it when I come home.

When we lived in Brussels, he says, there was a road that went through the country all the way out to the area of the Pale that Irving came from. Once, when my grandfather came to visit us, my dad offered to drive out there. Surely he would want to see where his father was from.

No, my grandfather said. He left for a reason.

I used to struggle with the idea of visiting Eastern Europe. I wanted to see where my family came from, but I didn’t want to go, really. I’ve never had any interest in seeing concentration camps or other markers of the Holocaust in person. Everyone in my family was out of Europe years before the genocide, but it blotted out our history too. Because of the Holocaust I will never be able to find the graves of my ancestors. Because of the Holocaust I will never be at ease in their countries. They were probably never truly at ease either. Diaspora means unsettlement follows you. The ground beneath your feet was not meant for you. If I ever set foot in Eastern Europe I will know none of it was ever meant for me.

After all, he left for a reason.

vii. Tevye Performs a Farce

Three of my university friends are visiting. They want to see a Broadway show and settle on Fiddler on the Roof. I say I’ll come along; I’ve heard good things about this production from people I trust and, besides, how could I say no to anything about a Jew? Anything born of Sholem Aleichem’s mind? I’ve read Ruth Wisse’s criticism of Fiddler and, as a student of the original stories, I can’t say I disagree, but God knows I love a tearjerker.

I laugh at some jokes most of the audience remains silent for. When Tevye sings “If I Were A Rich Man,” I wonder if what sounds like gibberish is actually Yiddish. (I learn later it’s meant to approximate Hasidic chanting.) I wait, breathless, as the story builds.

This is a sad musical. It is a beating heart alone in the middle of an abyss. It is love in the midst of despair and desperation. Tevye and his daughters live a hard life and they break his heart three times, but he loves them, he loves them so painfully and so much. He loves them — even Chava, in the stories — above tradition, maybe above God. It tricks you; so much of the first half is joyful and funny and musical, and then: the wedding. The constable arrives, as he always does. I think of something a professor told the class about why Jews didn’t leave Nazi Germany: We always think of our persecutors as Haman. We always defeat Haman. So Hitler was another Haman; people thought things would blow over. Your house is burned down but you still have your life. You still fiddle and sing.

It’s like Karl Marx says: Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce. It’s like André Aciman says: Everything in history happens twice, wrote Marx, the first time as tragedy, the second as farce. He forgot to add that Jewish history is repetition, the history of repetition. It’s like Tevye says: A Jew must never, never give up hope. How does he go on hoping, you ask, when he’s already died a thousand deaths? But that’s the whole point of being a Jew in this world!

I cry in the swelling silence as Tevye stares at the destruction. I don’t know if my great-grandfather ever saw a pogrom. It seems more than possible. He left for a reason. I cry when the constable comes to expel the Jews. I cry when they leave their homes.

We walk out, and I think about Irving and his family. He left for a reason. Did Tevye look over his shoulder at Boiberik when he left? Did he ever think his daughters might go back? He left for a reason — surely. Did somebody tell my great-great-grandfather lekh-lekho?

Jewish history is the history of repetition, and it is the history of unanswered questions. He left for a reason. My great-grandfather is dead, and his son has dementia. There is no answer anyone can give me that will tell me the emotional truths of what I want to know. A thousand deaths, and no one can tell me what came before.

I lie awake at night thinking about Sholem Aleichem. I think about Tevye, who loves his daughters so much he would leave his home forever for them. I buy my own copy of Tevye the Dairyman. And it still runs through my head: He left for a reason.

Chloe Sobel graduated from Queen’s University and is editor in chief of New Voices.