I know when those sleigh bells ring, that can only mean one thing: the sound of forced assimilation.

If you’re on the internet and move in Canadian or Drake-loving circles, you’ve probably seen the usual “Hotline Bling” memes, now featuring Christmas. You’ve seen the ugly Christmas sweaters with Drake’s likeness on them. They’re harmless, I suppose, and the cost of becoming a meme, but I wince every time I come across one.

Drake and I are very, very different people, but we have this in common: We are both from interfaith backgrounds, and we are both Jewish.

I won’t pretend to know what Drake thinks about all this. I do know that he owns his Jewish heritage, and I also think we have some of the same anxieties about our background. “You & the 6” is dedicated to his Jewish mother, and includes the tell-tale line: “I used to get teased for being black / And now I’m here and I’m not black enough.”

I’m white, so this is a specific part of Drake’s life I won’t pretend to understand. But I do get what it’s like to feel too ___ for ____. To feel the pull between two cultures that both want you and yet don’t.

Growing up, I’ve had to navigate two wildly different families: one primarily Southern Baptist and from Louisiana, the other Jewish and from New York. For a long time, my parents had a welcome mat that said “Shalom Y’all,” a symbol of our mixed cultures.

I’m solidly Jewish at this point in my life — Hebrew school until the age of twelve, bat mitzvah at thirteen, a seat at High Holy Days services every year, and, well, a job at a Jewish publication — but still I can’t escape the specter of intermarriage, of what it’s like to be half Jewish and also completely, wholeheartedly Jewish. Of what it’s like to not be visible.

The Jewish community didn’t want Drake, and it still wouldn’t if he wasn’t famous. It doesn’t want me. Despite the increase in the number of mixed-marriage children who identify as Jewish — among millennial Jews, nearly half of us are the children of intermarriage, and 59% identify as Jewish either by religion or by culture — the organized Jewish community still thinks intermarriage will be its death. Community leaders are still trying to decrease intermarriage rates and convert Jews’ non-Jewish spouses.

I have news for the organized Jewish community: The war on intermarriage has already been lost. You never needed to fight it in the first place.

Because Drake exists, and I exist, and so many other Jews like us exist. When I had my bat mitzvah, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to be Jewish. Now I’ve minored in Jewish studies and I work at a Jewish publication. I’m the future, not the end.

I’d speculate that Ashke-normativity and the fear of intermarriage are tightly linked. Part of how the community battles intermarriage and assimilation is to urge us to marry within the tribe. For the vast majority of Jews in the United States, that’s Ashkenazim. Whether or not you think Ashkenazim are white, and whether or not individual Ashkenazim look more Eastern European or more Middle Eastern, that works against intermarriage not only of the religious kind but the racial. If both of your parents are white or white-passing Jews, and if you grow up in a religious community unfriendly to intermarriage, it becomes much harder to imagine a Jewish community in which Jews of color and/or religiously mixed heritage not only exist but are welcome.

It wasn’t until I went to university that I began exploring my Jewish identity more. I made friends with other Jews who had struggled with their identity for various reasons, and I was able to move fully past the time a teacher at my Reform synagogue had told me he’d never officiate an intermarriage. (I can’t help but think that maybe if the community accepted intermarriages and their offspring more readily, we would identify more strongly as Jewish?)

Yet I still can’t shake the feeling, whenever I’m around a group of other Jews, that I don’t fully belong. When I mention my mother is a gentile, I try to do it casually, and I try to enforce my own Judaism and Jewishness as much as possible. When I’m with gentiles, I do the same thing — not because I’m afraid they’ll reject me as insufficiently Jewish, but because if I don’t remind them, they’ll forget that I’m not one of them.

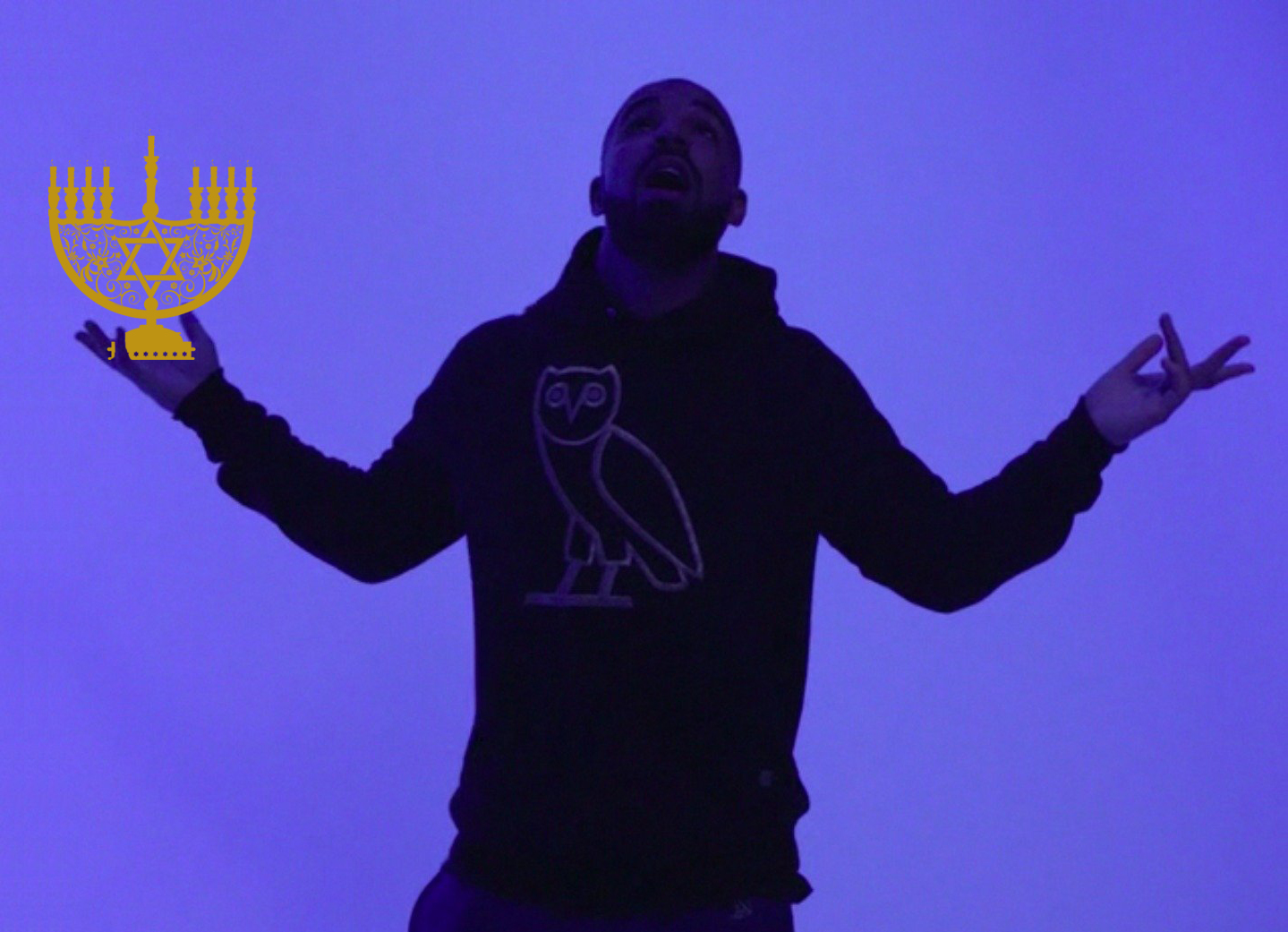

So to see Drake, a fellow child of intermarriage, being subsumed into wider Christian-normative pop culture when he so proudly and literally wears his Jewish identity is upsetting. I see myself in that, no matter how flawed the comparison. There is a space that we occupy in between the organized Jewish community that doesn’t want us and the gentile community that only wants us if we don’t wear a Magen David on our sleeve. The space we have found is still Jewish. I’m staying here. Let Drake stay here too.

Chloe Sobel graduated from Queen’s University and is editor in chief of New Voices.