When I was a day school student, Yom ha-Sho’ah, or a Holocaust Memorial Day was a yearly occurrence. Every year, there were assemblies and meetings with Holocaust survivors, and it was all followed by what I assumed was survivor’s guilt. Following Passover, I inevitably felt like the Wicked Son at the seder: not on in the sense that I was asking what this had to do with me, but because I felt bad for not feeling guilty enough. Perhaps I came out of Holocaust Memorial Day programming feeling the way I was supposed to: filled with different emotions, but one overwhelming emotion of guilt. Yesterday we were slaves in Egypt; today we are free, but I, having grown up in middle-class America, had known little enslavement.

Judaism seems to be obsessed with memory — specifically, our collective memory as a people and as a religion. We are commanded to remember (as well as to not forget) Amaleq, the biblical nation that was the first to attack the Israelites after their leaving Egypt. We are told to remember Egypt, and we hearken back to the notion of being liberated from slavery, both during prayer and various rituals. We are told to remember the Purim story, which is why it was recorded as a megillah, a scroll. And, finally, we are charged with remembering the Holocaust.

What, however, does remembering do to us? What are we supposed to do with the collective memories that we, as two or three generations removed from the Holocaust, are being given? Certainly, the memory of the Holocaust is far more real to me than any memory of leaving Egypt or the threat of annihilation in Ancient Persia, but that does not make it easier to relate to — it just means that I am able to see the direct consequences of the Holocaust on Judaism today. For me, the Holocaust has a far greater impact than Ancient Egypt or Persia did.

But this does not give me anything other than just the memories imparted to me. Implicit, it seems, but never stated, is not just the requirement to remember, but ways to remember. Stories and personal accounts are important, to be sure, and are valuable resources. But are we keeping that memory alive if we aren’t doing anything with the memories we have been given?

In some cases, like those recorded in the Bible, there is a connection between remembering and taking action. We are commanded to be kind to the stranger in our midst because we, too, were strangers in a strange land, and have within us the collective memory of being outsiders, oppressed, and lacking privilege in society. Thus we are charged with finding ways to remember in ways that go beyond reading names and lighting candles.

What makes these memories come alive is not the presentations and the songs, but what comes afterward. We, as Jews, are survivors, but that means that we must make sure others are not also placed in similar situations as we were. This Holocaust Memorial Day, we should not only remember, but move beyond remembering, making sure that we, as survivors, are among the last to be such victims of the violence that we commemorated yesterday.

Our collective memories need to be a call to action. This action needs to be one that brings the Jewish community together and unites us in a goal to make sure that we are the last ones to be strangers in a strange land, and the last ones to be oppressed. It is time to move beyond the institutionalized survivor’s guilt to move toward a collective action and use our guilt for something constructive. Guilt is not a productive emotion, and is no more useful in the collective conscience of a community.

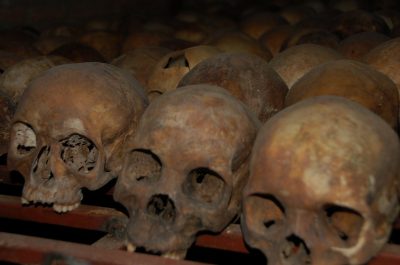

This means that if we truly want to remember the Holocaust, we must become sensitized to genocide and violence being committed against other minorities around the world today. It is time that we turn our remembrance of the Holocaust from one of guilt and debilitating fear to a call for action. Our fear of history repeating itself is only productive if we work to make sure it does not only repeat itself for us, but that others do not face the violence that we did.

Yesterday, Yom ha-Sho’ah, was the day that we remember what happened to Eastern European Jewry. Today is the day we turn toward the world and use this as a call to action to make sure that the genocides happening around the world are put to an end. Now, it is upon us to lobby, to speak up and to demand change, even if we are thousands of miles away from the conflicts.

Amram Altzman is a student at List College.