The fenugreek sprinkled into the chicken coconut stew has no significance to the half-dozen diners scattered around the restaurant. But to Thoufeek Zakriya, an Indian Muslim, the plant is not just a staple in Indian cuisine — it is an artifact in the history of Cochin’s Jewry, the long tale of a small community in the port city of Kochi in the Indian state of Kerala.

Fenugreek is also called uluva in Malayalam, the language of the area in which Cochin is situated. “A similar dish is found in Yemeni Jewish cuisine, but different in taste and flavor,” Zakriya explained. “The name of the Yemeni dish is hilebah. In Indian languages, when you look at the translation for fenugreek — only in Malayalam is it uluva.” Use of the plant links Cochin’s Jewry to their Jewish identity.

Tracing the origins of uluva was just one stop on my journey to discover Jewish life in Cochin that would come to include one man’s self-taught talent for Hebrew calligraphy and the presentation of a handmade cake bearing Hebrew greetings to Israeli businessmen.

His Growing Fascination

Zakriya’s fascination with the Jews of Cochin started as a 10-year-old when he asked his father to take him to the synagogue in Jew Town, Cochin’s Jewish quarter. At the time, Zakriya did not know that Jews first settled in Kerala, the state in South India where Cochin is located, over 2,000 years ago. He had yet to discover that Jews from Yemen, Iran, Iraq, Spain and Portugal began immigrating to India in the early 1600s. He had no idea that he would become close friends with the town’s elderly Jewish residents or become a colleague of historians that study Cochin’s Jewish community. He was just a curious 10-year old.

“My classmate at school went to the synagogue. He was explaining the details and I was so curious. I just wanted to see it. I insisted to my father that he take me there,” he said.

Young Thoufeek was moved by the 500-year-old synagogue’s blue tile floors imported from China and its clusters of low hanging chandeliers.

“It was like watching a movie. There was a yellowish tinge, there is still a picture in my mind. It was an enchanting feeling like going into a new place.”

Seven years passed before Zakriya returned to Jew Town. In the meantime, Zakriya devoted himself to his schoolwork and taught himself different types of art. He made plaster sculptures of the elephant-headed Hindu god Ganesh but stopped once he realized constructing idols clashed with his Muslim beliefs. He then dabbled in painting.

Zakriya’s urge to learn more about Judaism resurfaced as a teenager when he studied at his local madrasa or Islamic religious school. The main teacher of the school would talk about biblical figures like Abraham. It inspired him to learn more about the history of Islam and study the similarities between Islam, Christianity and Judaism.

“It was opening for me to know more about my religion [and to] learn about the sister religions,” he said.

Zakriya quickly realized that he had more than a passing interest in the stories that his madrasa teacher told from the Torah. Finding a real Hebrew Bible was the best way to continue his studies.

Eventually, a teacher at Zakriya’s high school gave him a Gideon Bible from the school’s library. His favorite part about the it was the title page, where Bible passages were printed in over 25 languages. He recognized the passages in French, German, English, Spanish and Tamil, but was puzzled to see Hebrew script. It was the first time he had ever seen it. Enchanted by the script, Zakriya made it his mission to learn how to write Hebrew.

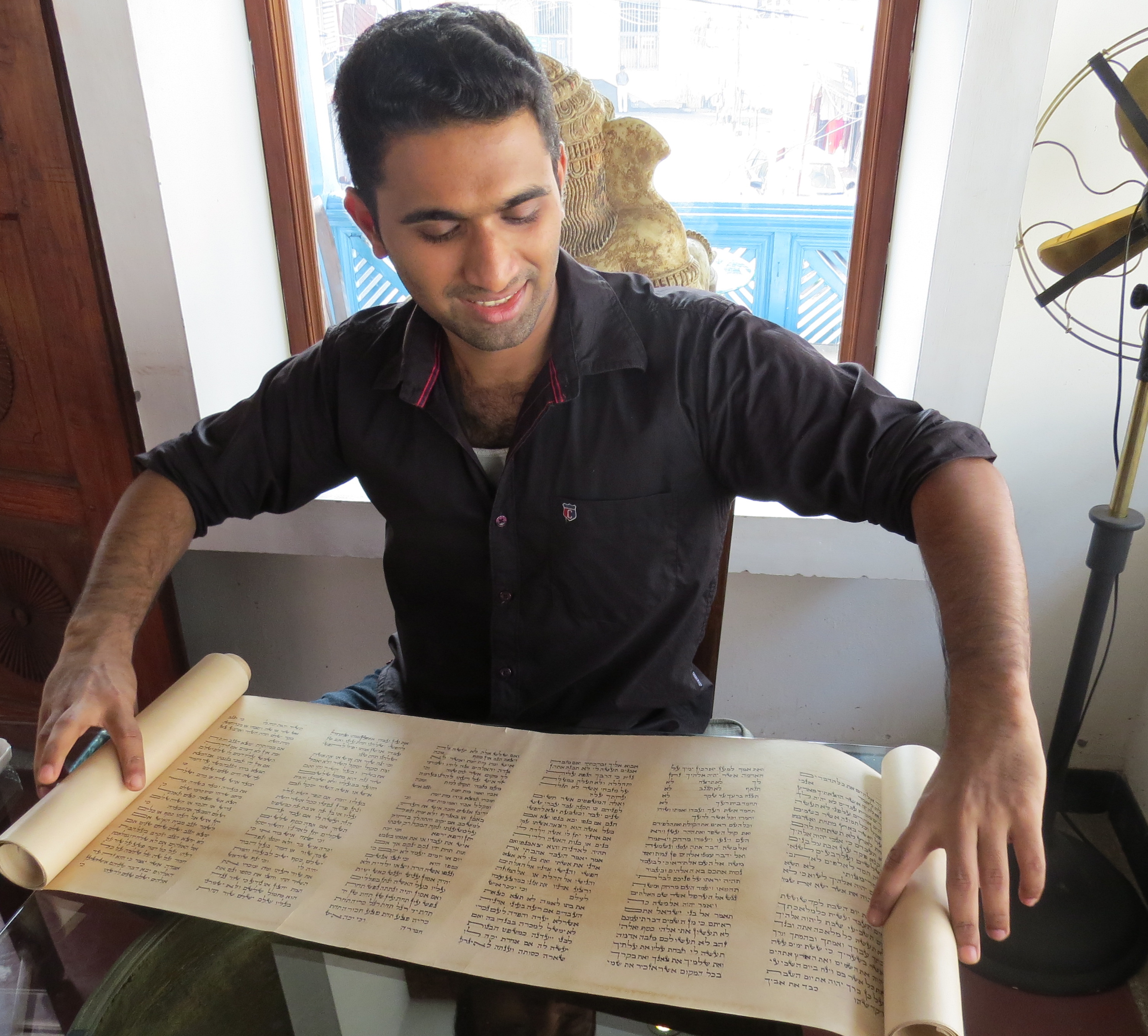

The Gideon Bible became his Hebrew writing textbook. Zakriya started writing Hebrew calligraphy with an ink pen, and gradually moved on to feather pens, bamboo tips and, finally, calligraphy pens. He filled over 1,000 pages with Hebrew and Arabic calligraphy. (Zakriya learned Arabic calligraphy while learning Hebrew calligraphy and also does calligraphy in Aramaic, English, Samaritan and Syriac.)

“I didn’t even know about the name or word calligraphy when I first started,” he said. “This particular art form gave me a special kind of joy. When I write and see myself I feel so happy,” he said.

After Zakriya felt he got everything he could out of the Gideon Bible, he obtained a Hebrew prayer book by badgering the booksellers at Cochin’s waterfront for weeks. He learned how to read Hebrew by copying the English transliteration of the Kaddish prayer

“It’s a combination of a spiritual and artistic experience when I do calligraphy. I feel like I am touching ancient times. It’s just like a time machine,” Zakriya said.

Studying Hebrew calligraphy has redefined and given more meaning to the way he practices Islam. Growing up, Zakriya would recite the Quran before bed and would silently pray as he meandered through the streets of Cochin.

“Judaism and Islam are not that different for me. At a deeper level, everything is basically the same,” he said. “I am very close to God. I consider him a friend.”

His Adopted Bubbe

“He has become like a child to me. He knows everything about me. [It’s as if I] made him a Jew,” Sarah Cohen said of her Muslim friend as she lounged in her wicker recliner. Cohen’s maternal family came to India from Baghdad.

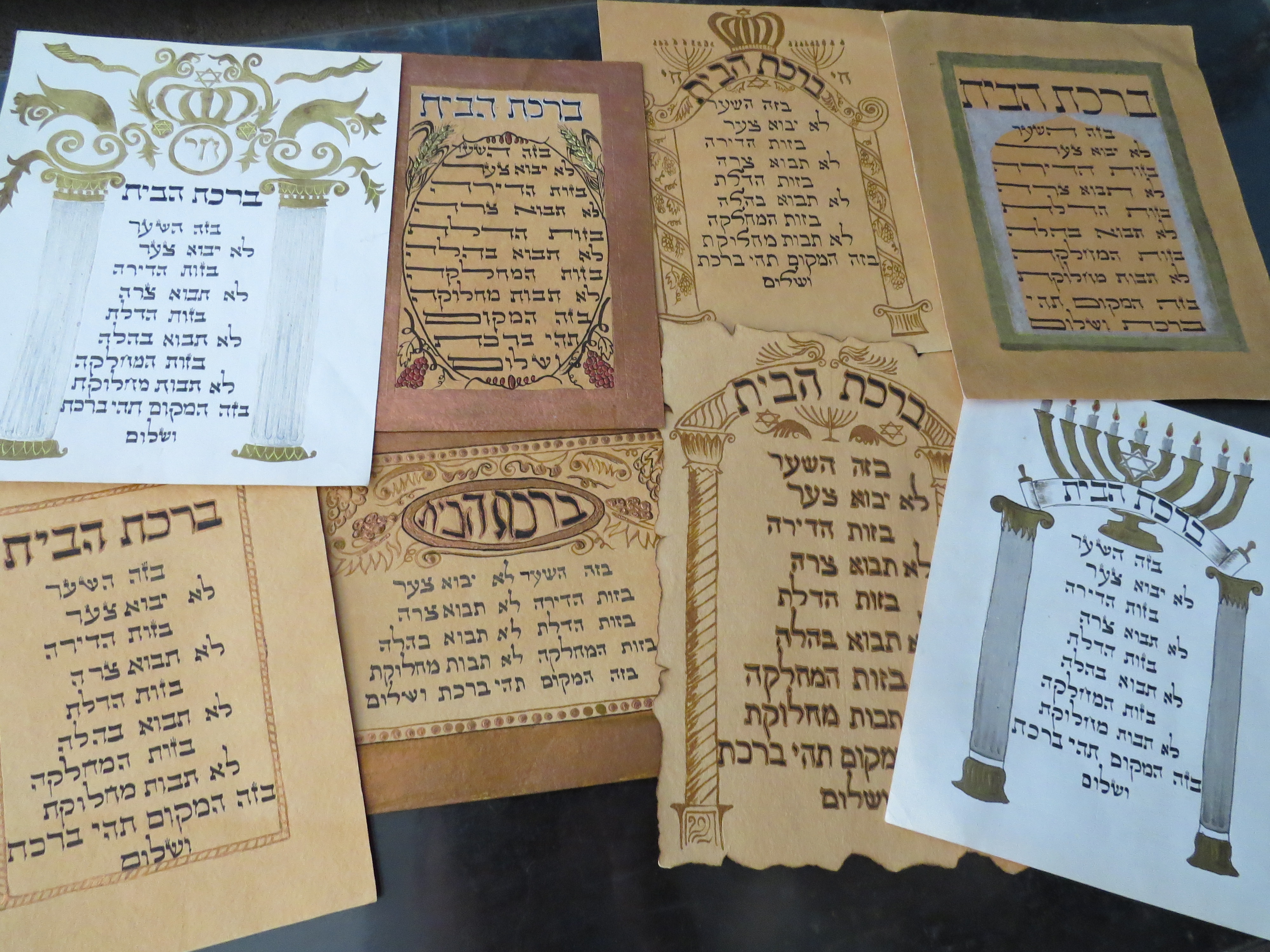

Cohen, 90, is the Jewish grandmother Zakriya never had. Zakriya first met Cohen when he took a friend to the Jewish Quarter. At the time of their meeting, his dedication to practicing Hebrew calligraphy numbered in the months. Cohen was astounded when he showed her a parchment of the Birkat Habayit, the Blessing for the Home. Eager to learn more about Zakriya, Cohen invited him inside her shop for tea.

“She was so surprised to see that I spoke and wrote Hebrew. It seemed like she asked me if I was a Jew like 100 times,” Zakriya said about his first meeting with Cohen.

What started out as a cup of tea turned into daily meetings between the elderly Indian Jewish woman and the curious Indian Muslim youth. They spent afternoons talking about food and Jewish dietary laws while munching on the deep fried cookie and crepe-like snacks called achappam and kuzhalappam. Other members of the Jewish community would drop in on their visits and share more stories about Cochin’s Jewish community. Eager to see Zakriya progress with his calligraphy, Cohen gave him a Venetian Tanakh printed in 1835.

“I used to ask her questions about Hebrew. She taught me how to cook. We made biryani [an Indian rice dish] on Fridays before Shabbat,” Zakriya said about the early years of his relationship with Cohen. “My own grandmother used to sarcastically tell me, ‘You go to Sarah Cohen and then come to me.’”

As Zakriya and Cohen grew closer, Cohen eventually became friends with Zakriya’s family. Zakriya’s parents and sisters celebrated Simchat Torah with Cohen and other members of Cochin’s Jewish community. Zakriya’s father, the owner of a fishing company, gave fish and fresh fruits to Cohen for Rosh Hashana.

Ultimately, Cohen wants to see Zakriya start his own family.

“I keep telling him to get married. I don’t know how much longer I will be around,” she joked.

Zakriya’s interest in Judaism is not limited to his art or his relationship with Sarah Cohen. It has become an interest that manifests itself in both his professional and personal life.

When Zakriya is not hunched over a piece of calligraphy or chatting with Sarah Cohen, he’s chopping vegetables and preparing curries at a luxury hotel in the Indian IT capital of Bangalore. A few months ago, when a pair of Israeli business travelers stayed at the hotel, Zakriya became their personal chef, preparing Israeli food for them. A few days before the guests were supposed to leave, Zakriya made them a cake that read lehitraot, a Hebrew goodbye, wishing them good health.

In addition to his calligraphy, Zakriya is an amateur historian. For the past two years, he has kept a blog about Keralan Jewry where he writes, among other topics, about a Cochin Jew working as a diplomat for the Dutch East India Company and the influence of coconut in Keralan Jewish religious traditions and cuisine. He discovered the presence of a Jewish quarter Malabar Coast city of Kozhikode by reading old travelogues and history books.

For Zakriya, studying Keralan Jewish history is not as unusual as it might appear. It’s an extension of his natural interests.

“I have a general interest in everything — let it be a piece of wood or a stone,” he said. “The Jewish community is a micro-community with its own identity and stories. If I studied about any other community it would be hard for me to get the details. But since this [the Jewish community] is close to my kind [citizens of Cochin and Muslims] it keeps me digging for more about the history.”

After our interview over chicken coconut stew and a meeting with Cohen, Zakriya hopped on his motor scooter and headed toward Cochin’s waterfront. He pointed out the bookstall where he bought the prayer book and stopped in front of a house with European architecture to explain how the home once housed Dutch traders living in Cochin during the 1600s.

If he could, Zakriya would spend all night talking about the history and Jewish history of Cochin. But he needed to go home and do an interview with a newspaper journalist and spend time with his sister’s newborn son. To the tourists and locals that Zakriya whizzes by on his way home, Cochin’s synagogue and Jewish quarter are just snapshots from another vacation or workday. But to Zakriya, they are integral parts of Cochin’s Jewish history — helping to form the history of the city itself.