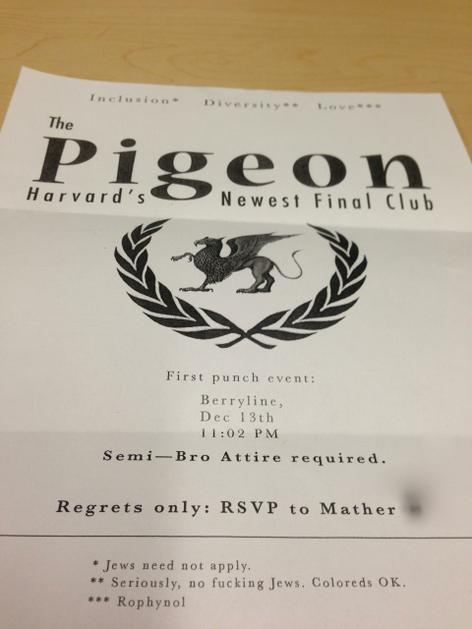

There is a long history of anti-Semitism at Harvard University, though it is essentially gone today. There is also a long history of subtle — and not so subtle — grandiose acts of satire at Harvard. Last Friday morning, students who live in Harvard University’s nine River Houses awoke to find that the intersection of those two Harvard traditions had been slipped under their doors in the night. It was an invitation to “The Pigeon,” a mock final club. Across the top of the flyer it said, “Inclusion* Diversity** Love***.” Following the asterisks down to the bottom of the flyer reveals:

* Jews need not apply.

** Seriously, no fucking Jews. Coloreds OK.

*** Rophynol [an apparent misspelling of Rohypnol, a date rape drug]

The anonymous author(s) probably meant to poke fun at the final clubs that have a long history at Harvard. If you went to Harvard — or if you saw “The Social Network” — you know that final clubs are prestigious invite-only undergraduate social clubs, a phenomenon unique to Harvard. Unless you’re just good at guessing where this is going, they also have a shaky reputation when it comes to racism and anti-Semitism. And, Harvard being Harvard, the otherwise minor incident of the flyer has sparked controversy and outrage far beyond the school.

Most people see the see the situation in one of two ways. Many believe that statements such as “Seriously, no fucking Jews” make the flyer unforgivable, promoting hate speech and so forth.

Others counter that the flyer, while uncomfortable, falls completely within the bounds of free speech and should be treated as such. Indeed, the only speech that really needs any protecting is speech that causes discomfort. Some see the flyer as exemplifying precisely that notion.

Evelynn M. Hammonds, Harvard’s undergraduate dean, responded with the following statement: “As an educator, I find these flyers offensive. They are not a reflection of the values of our community. Even if intended as satirical in nature, they are hurtful and offensive to many students, faculty and staff, and do not demonstrate the level of thoughtfulness and respect we expect at Harvard when engaging difficult issues within our community.”

We agree that they’re not particularly respectful or tasteful. So what? That’s not what satire is for. On the other hand, it’s not the cleverest example of satire the world has ever seen. As journalists and as editors, we twitched a little at the misspelling of Rohypnol — but we’ll get over it. If we were Harvard administrators or faculty, we would probably see the flyers as poor reflections of the Harvard educational enterprise. (We might also be more than a little dismayed one of the highest officials at one of America’s best universities can’t quite make out whether the flyer was “intended as satirical in nature.”)

That said, we do not really find the flyer particularly offensive either. It’s obviously a work of satire. The writers were attempting to point out what they see as enduring racial and religious discrimination within the final clubs. They might be right. They might be wrong. Either way, they — and we — are lucky to live in a country where all are allowed to say offensive things. At the same time, their point could have easily been made in a less in-your-face manner

The other important part of this is that the authors’ criticisms cannot be so easily dismissed. While final clubs and Harvard have certainly changed a great deal over time, Harvard’s history with regard to racial and religious discrimination is far from rosy. In 1922, when Jews constituted 22% of Harvard’s population, President Abbott Lowell took steps to drastically reduce that number. He instituted an “aptitude and character” evaluation as part of the college process. This may seem like an admirable addition at first, similar to modern recommendation letters, but one of the major goals of this character test was to more adequately obtain data regarding which applicants were Jewish, so that Harvard could bring that number down to something more palatable. When Lowell left in 1933, Jews were 10% of Harvard’s population.

The extent to which Harvard’s final clubs lagged behind the university in diversity is well-documented. While Harvard’s first black graduate received his diploma in 1870, it took almost a century, until 1965, for the first black student to be welcomed into a final club. The Porcellian, often depicted as the most prestigious final club, waited until 1983 to admit its first black member. We’re not in a position to speak about the extent to which discrimination is still present in the final clubs. But if there are students are Harvard who find the issue worthy of a highly visible display of public satire, we assume the issue still merits consideration.

Ultimately, if we had woken that morning and seen this flyer, we would have read it, half-heartedly chuckled and continued on with our lives. We suggest everyone else do the same.