Read the following sentence, from the cover story of this month’s Utne Reader:

On the trail of decoding attention, Mike Posner–unarguably the greatest attention scientist of our time–is invariably two steps ahead.

Now, try this sentence:

On the trail of decoding attention, Mike Posner–the greatest attention scientist of our time–is two steps ahead.

It’s the same sentence as the one above, minus the two adverbs, but it makes a stronger case: the author wishes to claim that:

a. Mike Posner is the best attention scientist and

b. that he’s at the vanguard of the field.

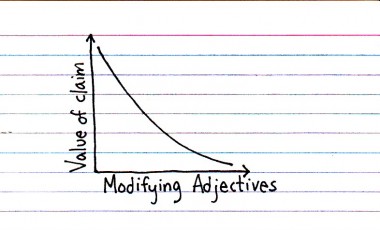

Each adverb, however, counteracts its respective claim: by writing that Posner is unarguably the best, I infer that there could have been an argument about his abilities. I have no idea what the author added by including invariably; all it does is delay the point of the sentence.

I learned in high school that writing equals “maximum meaning in minimum space,” in the words of a teacher of mine. Like in the above sentence, adverbs mean more syllables and less certainty: had the author written that Posner is the best attention scientist and that he’s two steps ahead, I would have had no reason to argue. I assume the author knows more about this subject than I do (which is why I’m reading the article) and I haven’t heard of Mike Posner.

Let’s get more radical. Consider this version:

On the trail of decoding attention, scientist Mike Posner is two steps ahead.

There goes the neighborhood, right? Wrong. The claim doesn’t change: in eight fewer words we learn that Posner is at the forefront of the attention field. We miss, in this version, that he’s preeminent in the field, but we don’t need to know that. By the author’s telling us that he’s two steps ahead we understand that he’s got the skills, and isn’t the whole point of science that you don’t need a pedigree in order to make a difference, that research can stand on its own? It doesn’t matter whether Posner was good at attention science years ago; what matters is that he’s good now. And this version of the sentence emphasizes the metaphor of being ahead on the “trail of attention.” In the first version we lost that with all the words in the middle.

Adverbs and adjectives have their place: peruse my past blog posts and you’ll see that I’ve used some–and that’s nothing compared to when we talk, where every other word is a really or a just. Adverbs and adjectives make our lives easier by giving us a crutch when we don’t have the time or energy to think of a stronger verb or noun, as none of us do when we’re talking to each other. But writing is different. We write so we can have measured thoughts and chosen words, so we can express ourselves without the burden of conversation. Writing is no place for laziness: it needs no crutch.

But the best writers write like they talk–or like their readers talk, which is why some modifiers do make it into any piece of prose (and into this sentence). And that’s OK. What’s not OK is using words like unarguably or invariably, which I forgot existed until I read this article. If you don’t hear a word in your day-to-day, there’s no reason to put it in an article, or any piece of popular writing.

I know that I’m being nitpicky. I know that 87% of people who started reading this article stopped after realizing that they were in for an English lesson of over 600 words. But the point is larger than grammar. It’s easy to add words when we can’t think of the right one, or to cast doubt upon your claim in order to keep yourself safe should someone attack it. Hide behind the adverb, and they can’t get you. In this world where people are always writing and always linking, attacking each other in the blogosphere and on the cable news channels 24/7, safety is appealing.

But we don’t need safety in our writing; we need certainty. And we don’t need five blog posts with five hundred words each, written in thirty minutes each. We need one post where the author took those two-and-a-half hours and used them to think about the words she wrote and the thoughts she expressed, to make a point she was proud of, a point she could defend without retreating behind a slew of probablies, arguablies or inarguablies–because if the point was good, why argue?

And the image above is from this blog. Props.